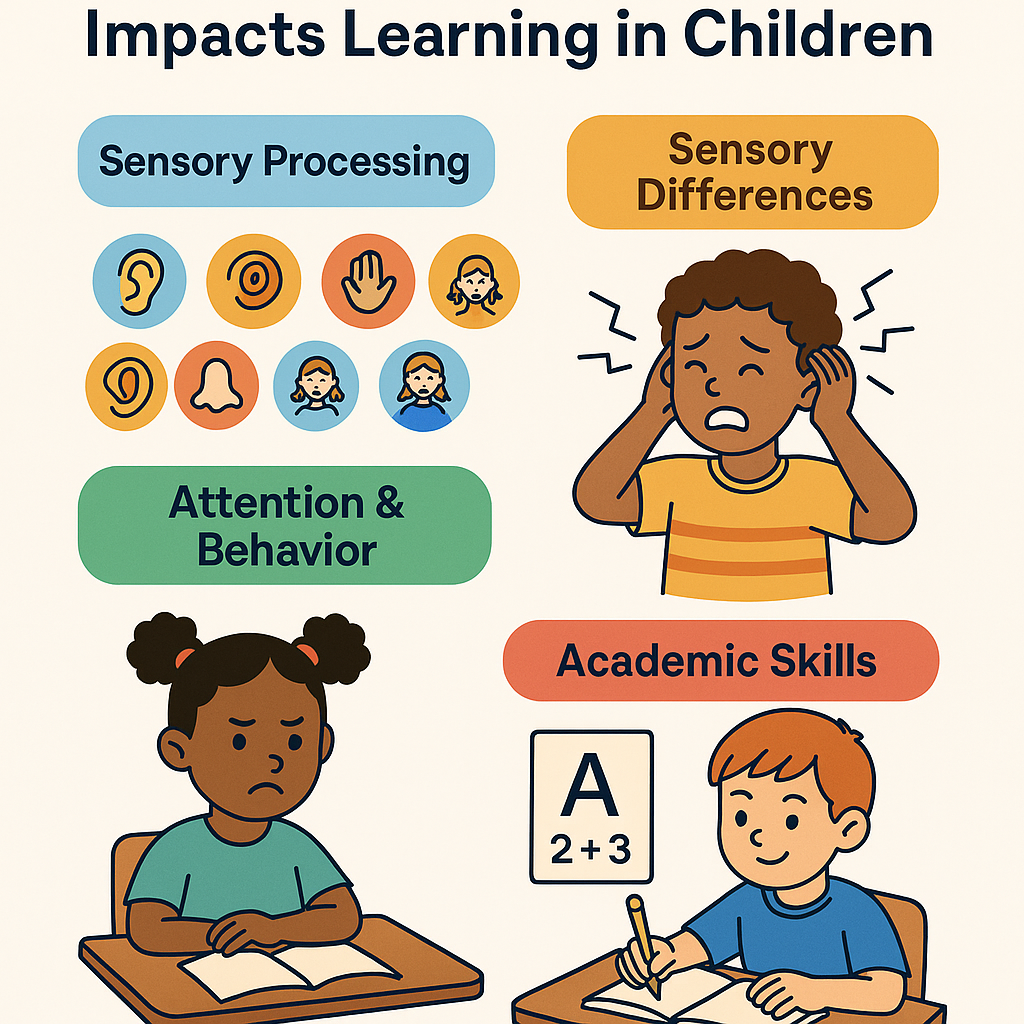

How Sensory Processing Impacts Learning in Children

Learning isn’t just about absorbing facts or memorizing content—it’s built on a foundation of sensory processing. When the brain can efficiently receive, filter, and respond to sensory input (from touch, sight, hearing, movement, body awareness), children can stay focused, regulate behavior, and engage meaningfully in learning. Conversely, sensory processing challenges can disrupt attention, motor skills, academic performance, and social engagement.

In this article, we explore how sensory processing affects learning in children, present real strategies, and show how occupational therapy can make a difference.

What Is Sensory Processing & Why It Matters for Learning

Sensory processing describes how the nervous system acquires, organizes, and interprets input from internal and external senses (touch, proprioception, vestibular, vision, hearing, taste, smell). When these inputs are well integrated—i.e., sensory integration—the brain can filter irrelevant information, prioritize relevant signals, and support purposeful responses.

Without effective sensory integration, a child may struggle to select which stimuli to attend to and which to ignore. Over time, this inefficiency erodes working memory, attention span, and learning potential.

Sensory systems critical for learning include:

- Tactile (touch)

- Proprioceptive (body awareness / position)

- Vestibular (movement, balance, spatial orientation)

- Auditory (hearing / filtering sounds)

- Visual (light, contrast, motion)

- Oral, smell, taste (less direct but still impactful)

In research, sensory processing difficulties—sometimes referred to as sensory processing disorders (SPDs)—are described as impairments in detecting, modulating, interpreting, or responding to sensory stimuli.

In children, some studies estimate that 5–13% may show clinically significant sensory difficulties, particularly between ages 4–6.

Common Patterns of Sensory Differences in Children

Children with sensory processing differences often display one or multiple patterns. Recognizing these patterns is key for targeted support:

| Pattern | Behavioral Features | Learning / Classroom Impact |

| Over‑responsivity / hypersensitivity | Sensitive to touch, noise, lighting; overwhelmed by crowds | Easily distracted, avoids tasks, may shut down |

| Under‑responsivity / hyposensitivity | Doesn’t notice stimuli, slow to respond, high threshold | Misses cues, needs strong prompts |

| Sensory seeking / craving | Constant movement, crashing, touching everything, loudness | Disrupts class, fidgeting, high activity |

| Modulation difficulties | Fluctuates between too much and too little sensory input | Inconsistent attention, emotional dysregulation |

| Discrimination problems | Difficulty distinguishing textures, sounds, spatial cues | Impacts reading, handwriting, auditory processing |

Note: Children may show mixed patterns (e.g. over-responsivity in one system, under in another).

How Sensory Processing Impacts Learning & Cognitive Function

Attention & Cognitive Load

A child whose sensory system is overactive may struggle to “turn down” background stimuli (like ambient noise, lighting, or movement). The brain must then allocate extra effort to filter distractions, leaving fewer resources for thinking, comprehension, and memory. This increases cognitive load and diminishes learning efficiency.

Academic Skills: Reading, Writing & Math

- Reading / Phonics / Auditory Discrimination: Background noise or difficulty filtering auditory stimuli can make phoneme discrimination, blending, or differentiating sounds much harder.

- Writing / Fine Motor Output: Poor proprioception or tactile sensitivity affects pressure control, spacing, letter formation, copying from board, and legibility.

- Math / Spatial & Visual Skills: Weak visual-spatial processing or vestibular instability can interfere with aligning numbers, geometry, graph reading, or spatial estimation.

- Motor planning & praxis: Difficulty organizing movements in writing, drawing, or using tools.

Executive Function & Self‑Regulation

Sensory instability undermines self-regulation. A child may struggle with shifting, planning, working memory, or inhibiting impulses when sensory systems compete for control.

Emotional & Behavioral Responses

When overwhelmed by sensory input, children may display anxiety, frustration, withdrawal, meltdowns, or avoidance behaviors. Some behaviors interpreted as “inattention” or “defiance” may actually be coping strategies for sensory overload.

Research shows that in populations like autism, higher sensory sensitivity correlates with lower academic outcomes, even after accounting for IQ or ADHD symptoms.

Sensory Issues in the Classroom & School Setting

Signs to Watch For (Teachers, Parents, Therapists)

- Frequent covering of ears or closing eyes

- Avoidance of certain textures or materials

- Excessive shifting, fidgeting, or moving during seated tasks

- Difficulty during transitions or changes in routine

- Complaints about lighting, noise, temperature

- Inconsistent behavior across environments (home vs school)

- Trouble copying from the board or aligning tasks

- Messy or illegible writing

- Crashing, bumping, or seeking strong sensory input

Environmental Triggers & Barriers

- Harsh fluorescent lighting

- Echoing or high ambient noise

- Overcluttered walls or busy visuals

- Unpredictable transitions or start/stop cues

- Sudden sounds (announcements, bells)

- Shared seating or crowded areas

Practical Classroom Accommodations

- Seat away from doors or distractions

- Use natural light or softer lighting, reduce glare

- Provide noise buffers or permit noise‑cancelling headphones

- Minimize visual clutter; use calm wall displays

- Give advance warnings before transitions

- Offer alternative means to respond (verbal, typed, manipulatives)

- Create a “sensory break” or calm corner for regulation

- Integrate movement breaks / heavy work before focused tasks

These adjustments can free up attention and emotional regulation for actual learning tasks.

Intervention Strategies & the Role of Occupational Therapy

Assessment & Sensory Profiling

Occupational therapists (OTs) use tools like the Sensory Profile, Sensory Processing Measure, clinical observation, and caregiver/teacher input to map a child’s sensory strengths and challenges.

Sensory Integration / Sensory‑Based Interventions

Therapeutic interventions include structured sensory activities (swings, climbing, textured surfaces, proprioceptive input) to gradually train the brain’s ability to respond more adaptively. Evidence is mixed, but many clinicians find benefit when interventions are tailored, goal‑oriented, and monitored.

Sensory Diets

A sensory diet is a customized schedule of sensory activities (e.g. push/pull, joint compression, deep pressure) woven into the child’s day to keep regulation levels optimal.

Self‑Regulation & Metacognitive Strategies

Teaching children to self‑monitor (e.g. “I feel overwhelmed”) and to employ regulation strategies (deep breathing, breaks, fidget tools, movement) empowers them to manage their sensory state.

Collaboration & Environmental Adaptation

OTs collaborate with teachers and families to embed accommodations, environmental modifications, and strategies into daily routines. This partnership ensures transfer and consistency across contexts.

Monitoring, Adjustment & Generalization

As children progress, develop new skills, or change environments (e.g. grade changes), the demands on their sensory systems shift. Strategies must evolve accordingly.

Case Illustration

Layla, age 9, shows the following:

- Complains of “buzzing in ears” during classroom discussion

- Avoids tactile tasks like clay or finger paint

- Frequently gets up and walks around mid-lesson

- Her handwriting is chaotic, struggling with spacing

- Thrives when doing vertical tasks (whiteboard) but not seated

OT assessment finds:

- Auditory hypersensitivity

- Poor proprioceptive discrimination

- Motor planning weaknesses

Interventions:

- Seat her away from noisy vents, permit quiet headphones

- Integrate heavy work (wall pushes) before writing

- Gradual exposure to tactile tasks, with choice and adaptation

- Work with teacher: allow verbal responses or typed work instead of excessive writing

- Reassess termly; introduce new strategies as she transitions grades

Over months, Layla’s tolerance improves, she self-regulates better, and academic consistency rises.

Tips for Parents, Educators & Therapists

- Keep a sensory journal: log triggers (noise, light, transitions) and helpful strategies

- Provide consistent routines & count-down warnings before changes

- Schedule movement / heavy work breaks integrated with academics

- Use multimodal teaching: combine visuals, movement, touch, auditory cues

- Offer choices: e.g. “Do you want to use a stress ball or take a stretch break?”

- Create a sensory retreat spot: a calm zone with comfort items

- Communicate across settings: share sensory profiles with teachers

- Embed accommodations in formal plans (IEP / 504)

- Coach self-advocacy: teach children to recognize and articulate their sensory needs

Limitations, Evidence & Best Practices

- SPDs as a distinct diagnosis remain debated—some professionals see overlap with autism, ADHD, or learning disorders.

- Many intervention studies have methodological limitations (small sample sizes, lack of blinding).

- Sensory interventions should not work in isolation—they must be tied to academic, behavioral, and cognitive goals.

- Ethical practice demands ongoing monitoring, adaptation, and clear functional goals.

Thus, a balanced, evidence‑informed, and child‑centered approach yields the best outcomes.

Conclusion & Call to Action

Sensory processing is a silent but essential foundation for learning. When children’s brains struggle to filter, organize, or respond to sensory input, the downstream effects ripple through attention, behavior, motor skills, and academic potential. Recognizing sensory processing challenges as legitimate, neurologically based issues—not simply behavioral problems—opens doors to compassionate support and meaningful intervention.

At Haghighati Occupational Therapy Academy, we are committed to bridging neuroscience, therapy, and education. If you suspect your child faces sensory processing difficulties or want to strengthen classroom strategies, reach out. Our team can conduct assessments, design tailored sensory diets, collaborate with educators, and guide families on the journey toward balanced learning.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Can sensory processing issues be “cured”?

A: While sensory systems often mature and children adapt, many will benefit from ongoing support. The goal is not “cure” but functional improvement, regulation, and learning empowerment.

Q: Is sensory processing disorder (SPD) medically recognized?

A: SPD is not currently codified as a distinct medical diagnosis in many classification systems. But many clinicians use the term to describe clinically impactful sensory differences that require intervention.

Q: How early can we detect sensory processing challenges?

A: Some patterns emerge in infancy (e.g. feeding, tactile defensiveness), but comprehensive profiling typically begins around age 3–5. Early identification improves outcomes.

Q: How do sensory issues differ from ADHD or autism?

A: There is overlap. Many children with ADHD or autism have sensory differences. What distinguishes them is that sensory processing issues focus on integration of sensory input, while ADHD emphasizes attention/impulsivity, and autism involves social/communication elements. A multidisciplinary evaluation is ideal.

Q: How long before we see improvement with therapy?

A: That depends on the child, consistency of intervention, complexity of the sensory profile, and environment. Some changes may appear in weeks; others may take months or years. Continuous assessment is key.